In this topic we are going to look at some strategies to help you plan your assessments to increase the validity and reliability of the inferences that you draw from the evidence of learning produced during your course. If you are going to have confidence in the judgments that you make about learners and their learning, it makes sense to put some significant thought into how you come to those judgments. Lipnevich et al. (2020) report that over 78% of syllabi they examined indicated a reliance on summative exams for determining at least some of the grades assigned to learners, so it seems safe to say that exams are a popular assessment instrument, possibly because they are familiar to many instructors, they appear to be relatively easy to create and administer, and selected-response tests are super easy to score, especially if automated.

In this topic, however, we hope to equip you with some ideas and strategies for ditching your selected-response test. After all, it is unlikely to be giving you accurate information about the learning happening in your course.

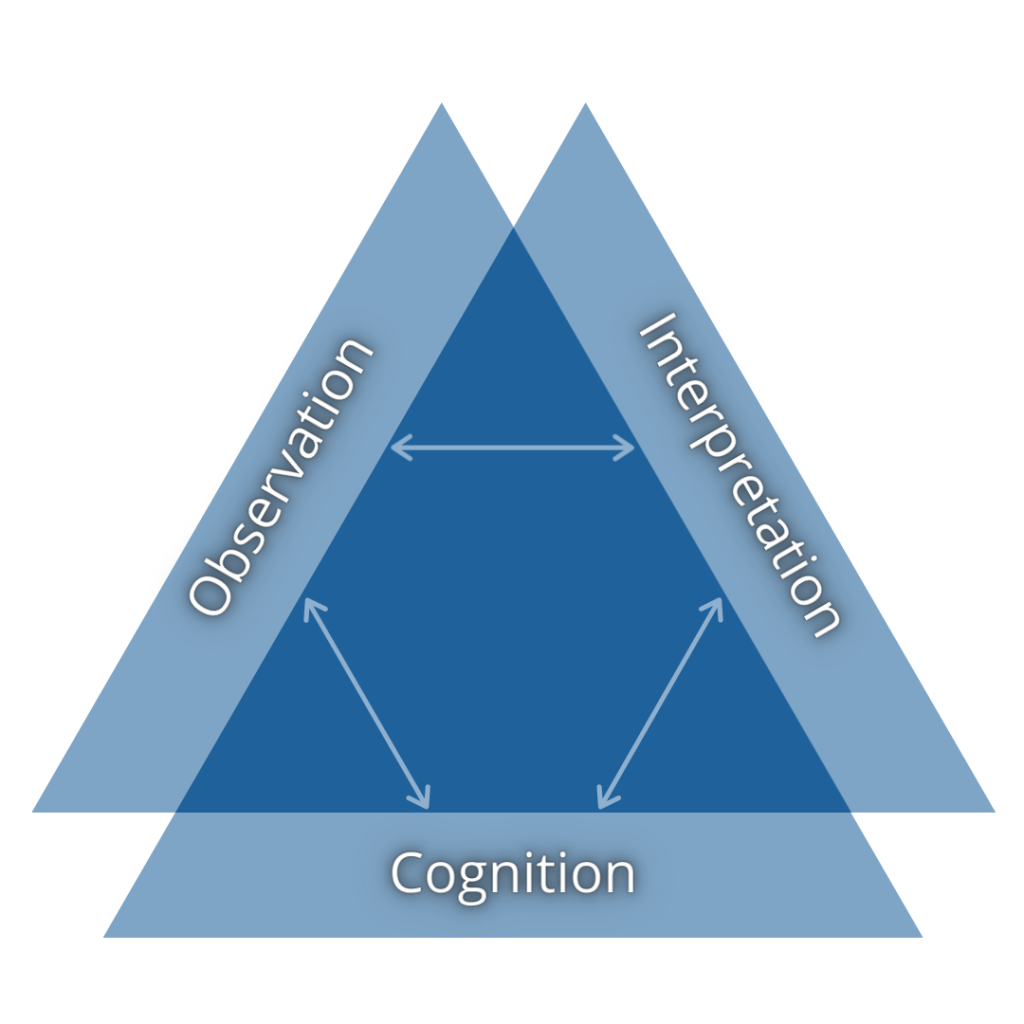

To begin, let’s think about the components of a well-considered assessment plan. The National Research Council (2001) writes about the idea of an assessment triangle comprised of three equal and interdependent parts: cognition, or a model of the construct to be learned; observation, a performance assessment of some sort, and; an interpretation, or inference based on the data gathered in the performance.

Assessment Triangle (National Research Council, 2001)

The assessment triangle is a tremendously useful tool in planning for assessment because it gives us a clear pathway from cognition to observation to inference, as well as clear guideposts to ensure that an assessment plan is properly aligned.

Cognition

The foundation of the triangle, cognition, is understood as a model of the knowledge and skills in a domain, mastery of which wold represent competence. This model includes not only the content of the domain but also how learners typically engage with learning the content and in which order. For example, learners typically learn addition prior to learning multiplication in mathematics. This model might be quite simple at early levels of learning, but extraordinarily complex as the ability level of the learners increases.

Most often, in designing learning experiences, this modelling takes place during the process of identifying and refining learning outcomes, at the very beginning of the process (although it may be a much more detailed process in some instances, such as for domains which require licensure, like nursing or accounting). Engaging in this process clarifies the domain of the course or learning experience and is both limited by the nature of the domain, and also delimited by the choices made by the instructor. The process also makes explicit the appropriate cognitive levels in relation to the outcomes such as learners being able to recall, describe, compare, critique, analyze, or create.

Observation

The NRC report describes the observation component of the assessment triangle as being a “set of specifications for performance tasks that will elicit illuminating responses from students” (2001, p. 48). It is critical that this performance task be directly and explicitly linked (aligned) to the cognitive model represented in the learning outcomes in order to ensure that the inferences derived from the data are valid representations of the learner’s ability in the domain.

In the design process, this is done by mapping assessments (i.e., performance tasks, portfolios, test items, etc.) to the learning outcomes and to the identified cognitive skill. For example, if an outcome is “Learners will be able to apply critical theory to issues related to gender in schools.”, then the assessment only requires learners to recall and describe critical theory, then there is a lack of alignment between the cognitive model and the observation of learner ability.

Interpretation or Inference

The NRC describes assessment as a process of “reasoning from evidence” (p. 42). As we learned in the previous unit, and reiterate here, measuring learning is at best an imprecise estimation. In large-scale assessments, psychometricians use detailed statistical models such as Classical Test Theory (CTT) or a number of different item response theories (IRT) to calculate the probability that a learner has obtained a particular level of ability in relation to the cognitive model. The trouble for classroom assessments, which are administered to groups that are much smaller than the required N. As such, classroom assessment inferences are more often inferred based on more qualitative or intuitive models.

The inferential model used in classroom assessments is important because the inferences we make form the judgments we communicate to the University with respect to how well learners have obtained the required knowledge or skills in the domain. In the design process, instructors should think carefully about the rubrics they use to guide their inferences and also about how much confidence they can have in their inferences.

Rubrics

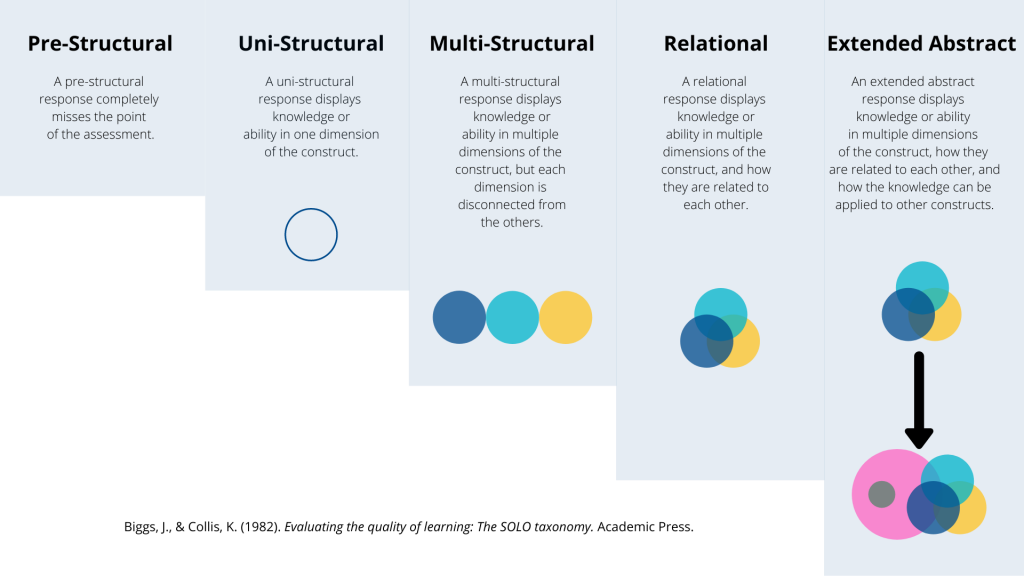

The UVic Undergraduate Grading Scale reflects a rubric that can be used to guide instructor interpretations of learner creations. It provides five clearly delineated categories (4 passing categories and 1 failing) of achievement and rich descriptions of each category to guide inferences. Another rubric that you might consider using is the SOLO Taxonomy (Biggs & Collis, 1982). SOLO stands for Structure of the Observed Learning Outcome, and it also describes five clearly delineated categories which can be used to guide inferences about student work.

The SOLO Taxonomy

Planning for Assessment: The Blueprint

In the next few posts, we will work through the process of blueprinting a course in preparation for developing and producing the content. Central to this blueprint process is ensuring that the cognitive model of the domain of your course is in alignment with the observations you will make which will provide evidence to support your inference, leading finally to a judgment in the form of a letter grade.

Optional Further Reading

Read Chapter 2 of Knowing What Students Know: The Science and Design of Educational Assessment, available online for free at this link and compose a short post about something you found to be important, or unclear, or perhaps a question you have on the backchannel. This might be a great time to join the backchannel (if you haven’t already) and introduce yourself!

Leave a Reply