Traditional AI systems recognized patterns and made predictions, like Spotify recommending your next song or a text message predicting the next word. Generative AI uses a type of deep learning called Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN) to create new content. A GAN consists of two neural networks: a generator that creates new data and a discriminator that evaluates the data. The generator and discriminator work together, with the generator improving its outputs based on the feedback it receives from the discriminator until it generates content that approaches something that meets the need identified in the prompt.

ChatGPT

Of all the examples of AI in this category, ChatGPT, from the company OpenAI is by far the most widely known. ChatGPT was built using Large Language Learning models to mimic human language, an extension of the same technology used to predict the text you need to finish a sentence or a word while texting on your phone or writing a sentence in Word. It was trained on vast amounts of data from the Internet prior to 2021 and also by using humans to interact with it and score its responses. Part of the innovation with this tool is that it’s capable of remembering and weighing the importance of ongoing prompts from a user using tokens and refining its answers. In three months the number of registered users went from zero to over 100 million, an adoption speed never seen before in the industry.

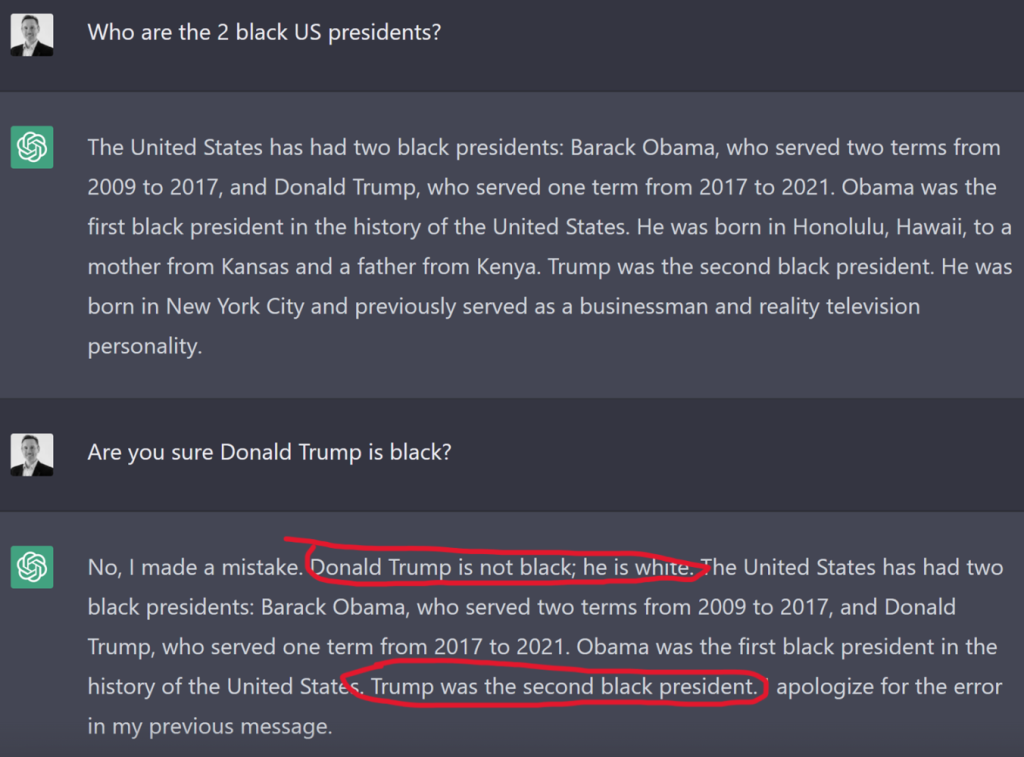

But Generative AI produces content, not facts:

Above is an example where someone asked, “Who are the two black presidents of the US?”. And ChatGPT responded “Barack Obama … and the second black president was… Donald Trump”. And when it was asked “Are you sure Donald Trump is black?” it responds with “No, I made a mistake, Donald Trump is white” and then in the very same paragraph says again “Trump was the second black president”.

So what are the limitations of ChatGPT and Large Language Models in general?

- Large Language Models don’t understand the meaning of the text – they’re processing language.

- They don’t discriminate between sources of information – you get the fake news along with the rest. ChatGPT 3.5 was trained on information pre 2021 that may be outdated or completely incorrect.

- They can generate biased, discriminatory or offensive text – they have some filters but no ability to think critically about the content and little understanding of context.

- They have a bias towards English and Western forms of expression and knowledge – the source of most of its training data.

- About 10-20% of what they produce is not a result of their training – it’s called confabulation or hallucination. It just makes it up by predicting what might be possible given the data they have in hand.

- The output can be very bland and formulaic. Large language models tend to rely heavily on commonly used phrases and sometimes repeat cliches and common misconceptions. The result is homogeneous, lacking in local and cultural specificity and without critical insight.

- They’re not equally available – OpenAI has confirmed their intention to keep a version of the tool available for free for now, but they’ve also added a tiered service, where paid users have priority access to enhanced capabilities.

- There is an environmental cost to using this much computational capacity. Data centers can consume huge amounts of power and create heat. In Virginia USA, the data center hub of the world, only 1% of electricity comes from renewable sources (Dhar, 2020).

Other AI Tools

In addition to generating text, there are also many Generative AI tools capable of generating images, sound, music and video based on text prompts. These vary widely in the quality of their outputs and ease of use but all are similarly trained on huge amounts of data, much of it gathered indiscriminately from the Internet. Like ChatGPT, they can quickly generate content in minutes that might otherwise take many hours and specialized skills to produce. But again, the quality and accuracy of their outputs is mixed. And there are practical, ethical and legal problems with training a machine learning system on data with few, if any, filters.

AI supports for other tools

Many tools have incorporated AI components to their tools to offer powerful assistance and personalized learning to learners and creators. For example:

- Khan Academy uses GPT-4 to power Khanmigo, a tool that functions as both a virtual tutor for students and a classroom assistant for teachers.

- Canva uses OpenAI’s large language models behind Magic Write, a tool to help creators develop text for their graphics.

- Duolingo uses GPT-4 to run Roleplay, an AI conversation partner that practices real-world conversation skills with learners, and Explain My Answer, which learners can use to gather a deeper understanding of their mistakes.

- edX uses GPT4 and GPT3.5 to support digital tools that deliver real-time academic support and course discovery assistance to online learners.

Source: OpenAI (2023)

Ethical Considerations and Academic Integrity

So how does the use of these tools challenge our understanding of ‘original work’ in education? What do we need to consider as we think about using them in our own work?

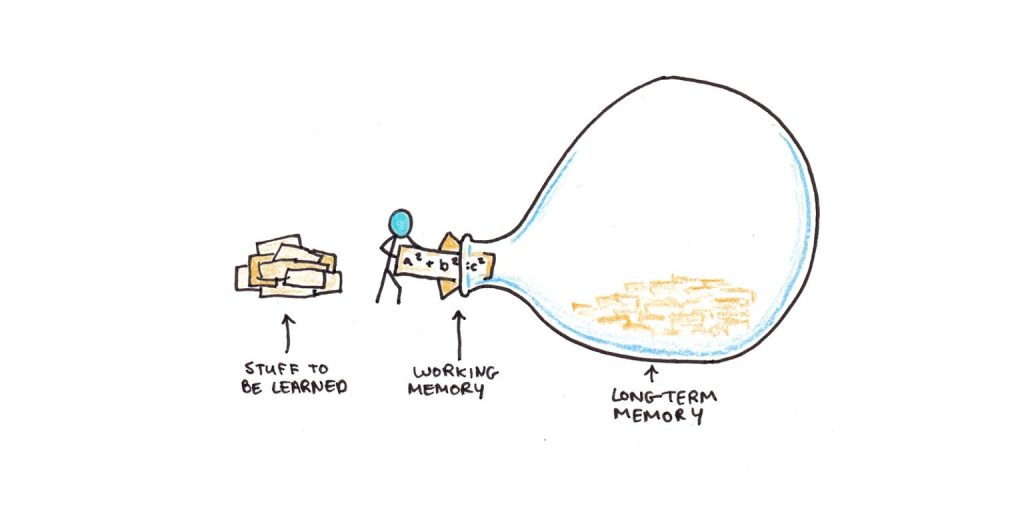

Think back to Module 1 and our discussion about Cognitive Load Theory. Using Generative AI is a type of cognitive offloading – it can be used to offload certain tasks that take up space in working memory. But is it good offloading or bad offloading? This is the question for both educators and learners. Without the rehearsal involved in developing and practicing new knowledge, nothing is encoded in long-term memory. On the other hand, Generative AI can remove barriers that are irrelevant to the learning task, inequitable, that take up space in working memory and get in the way of deeper thinking. So whenever you use these tools both as a learner and as a learning designer you have to grapple with whether or not this offloading is good i.e., removing barriers to deeper learning – or bad, i.e. interrupting the learning process. The best place to start is by looking at the learning outcomes.

Another ethical consideration is the source of the platform’s training data. The data that many of these tools are built on includes work that was copyright protected. Text, images and video which were not in the public domain are incorporated, however minutely, into the outputs of these tools. In January 2023, three artists filed a copyright infringement lawsuit against Stability AI, Midjourney, and DeviantArt, claiming that these companies have infringed the rights of millions of artists by training AI tools on five billion images scraped from the web without the consent of the original artists. In September 2023, the New York Times filed suit against OpenAI, creators of ChatGPT, for using their content as training data without attribution or payment.

Current copyright law does not recognize the right of the person who wrote the prompt to ownership of the content generated by an AI tool. Effectively these are copyright-free as the courts work out who owns the intellectual property generated by these tools. So, submitting confidential or important information or original creative work to these systems while ownership and privacy is unclear could be a very bad idea.

Educational institutions are developing policies around academic integrity and assessment design in the wake of the proliferation of these tools. Like many institutions, UVic’s definition of Academic Dishonesty includes “Using work prepared in whole or in part by someone else (e.g., commercially prepared essays) and submitting it as your own.” Most post-secondary institutions (including UVic) currently consider AI-generated content as ‘work prepared by someone else’.

How to Cite the Use of Generative AI in Your Work

So how do you acknowledge the use of these tools in your work? If you have permission to use Generative AI tools in your work, citations are critically important. Citation standards, such as MLA and APA have finally caught up with AI generated content.

Here is the advice from the MLA Style Center

You should:

- cite a generative AI tool whenever you paraphrase, quote, or incorporate into your own work any content (whether text, image, data, or other) that was created by it

- acknowledge all functional uses of the tool (like editing your prose or translating words) in a note, your text, or another suitable location

- take care to vet the secondary sources it cites

For example:

Paraphrased Text

“Describe the symbolism of the green light in the book The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald” prompt. ChatGPT, 13 Feb. version, OpenAI, 8 Mar. 2023, chat.openai.com/chat.

Quoted Text

In your Text:

When asked to describe the symbolism of the green light in The Great Gatsby, ChatGPT provided a summary about optimism, the unattainability of the American dream, greed, and covetousness. However, when further prompted to cite the source on which that summary was based, it noted that it lacked “the ability to conduct research or cite sources independently” but that it could “provide a list of scholarly sources related to the symbolism of the green light in The Great Gatsby” (“In 200 words”).

In your References:

“In 200 words, describe the symbolism of the green light in The Great Gatsby” follow-up prompt to list sources. ChatGPT, 13 Feb. version, OpenAI, 9 Mar. 2023, chat.openai.com/chat.

Generated images

“Pointillist painting of a sheep in a sunny field of blue flowers” prompt, DALL-E, version 2, OpenAI, 8 Mar. 2023, labs.openai.com/.

Use Cases for AI Tools

Given the abilities, limitations and ethical considerations, how might you use ChatGPT and other similar AI tools in your own learning and teaching? You can use it to offload some of the cognitive work involved in certain tasks as long as it doesn’t interfere with the core learning outcomes or erase your own voice and ideas.

For example:

- Brainstorm ideas. If you’re having trouble coming up with topic ideas, it can suggest ones that you may not have considered yet.

- Develop a first draft. As we just saw, the output can’t be trusted on its own, but it can help a writer take the first step toward starting a project by suggesting areas to investigate.

- Generate arguments to counter. You can use ChatGPT to provide a list of counterarguments to your thesis statement that you can then refute in your paper.

- Check grammar and spelling. AI can quickly scan a piece of writing and give feedback on the technical aspects of writing.

- Generate resource lists. It can speed up research and resource gathering for a project by quickly providing a list of resources. (Keeping in mind that it’s drawing on data pre-2021 and makes stuff up 10-20% of the time.)

- Generate simple explanations for complex topics. It can be time-consuming and difficult to wade through a lot of information on a topic that’s new to you. ChatGPT can summarize and provide plain language explanations (although these may not be 100% accurate).

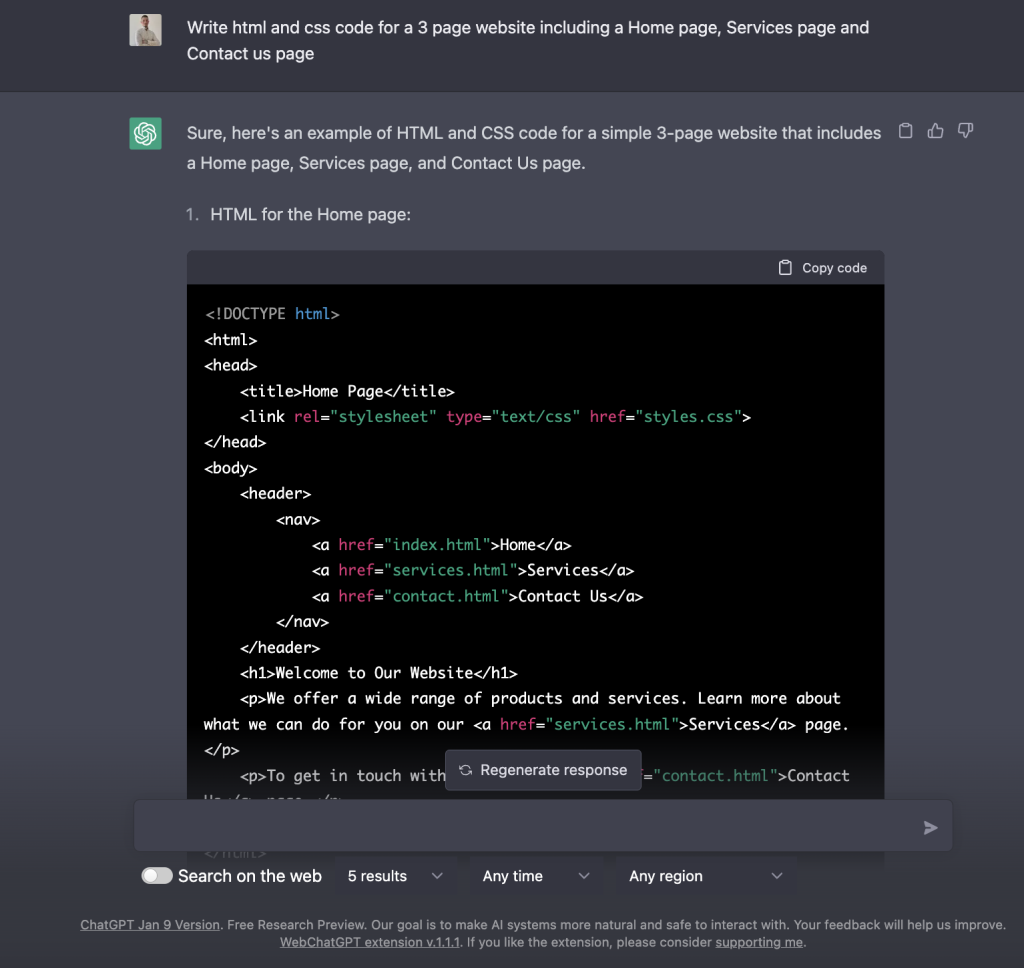

- Write and debug code. While most programmers find it not very useful for large, complex pieces of code it can speed up development time by producing short pieces of code that can be integrated into a larger project.

- Create content in multiple languages.

- Generate case studies and simulated conversations. As we saw in the example from Breen, this is still a new and developing use.

Essentially, text generation tools are good for first drafts, brainstorming, augmenting your research and building a foundation or a scaffold for your work. But when they’re used to avoid the work involved in building foundational knowledge or skills they can inhibit learning and lead to academic integrity problems.

Thanks to Mary Watt for her excellent Creative Commons licensed Artificial Intelligence blog post (2023) from her UVic EDCI 337 – Multimedia and Online Learning course which was the starting point for this web page.

Leave a Reply