Overview

Human beings have a rich tradition of storytelling as a method of transmitting learning and culture to the next generation, a practice as old as language itself. When we’re listening to a story – one that’s rich in detail and metaphor and includes compelling characters – research has shown that we tend to imagine ourselves in the situation. This has powerful implications for learning. In this module we take a look at some of the neuroscience behind storytelling for learning and explore some techniques that you can apply to your media and multimedia learning projects to maximize their impact. We’ll also take a look at Twine, a fun tool for creating and tracking branched interactive stories.

Recording your own video beyond a screencast, whether it’s with your laptop camera, your phone or a higher end camera, gives you the creative freedom to capture exactly what you need for your learning video. At the same time, it is a resource-intensive process that needs to be used strategically in your learning design. In this module, we look at the best use of this type of media resource and practice the planning and preparation that makes the process of video capture efficient and effective for learning.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this module you will be able to:

- Describe six promising practices for creating a meaningful story.

- Apply storytelling techniques to creating a short story with a learning purpose.

- Design a branched narrative using Twine

- Identify learning situations where the use of video would be most effective.

- Write a script for a short video focused on a story with a learning purpose.

- Create a simple storyboard for a short video.

- Apply Mayer’s principles to the creation of a short video for learning purposes.

Read/Watch

- Storytelling Techniques Used by the Most Inspiring Presenters (30 min) – A collection of storytelling techniques and short presentations by skilled storytellers.

- The Power of Story in Teaching (5 min) – An introduction to the benefits of storytelling in teaching

- Design Secrets of Interactive Storytelling (10 min) – Interactive stories are powerful learning experiences but more complex to create than you think.

- Effective educational videos | Center for Teaching | Vanderbilt University (15 min) – Applying Mayer’s principles to creating effective video for learning.

- How to Write a Script for Video (30 min) – Tips and templates for creating quick, effective video scripts (with a marketing focus, but still applicable to learning)

- Four Types and Four Goals of Learning Videos (30 min) – A teacher shares the four types of video that he creates for teaching and when they are most effective

- Filming and Editing Video (30 min) – A tutorial to help you plan and create a video.

Resources:

- How to Create a Storyboard using MS Word – A simple way to create storyboard templates

- Shooting Video on Your Phone – Vimeo has a good primer on how to capture the best quality video possible on your phone

- Twinery – Twine – a free open source tool for telling interactive, non-linear stories

- How to use Twine – (3:25)

- How to import images into Twine – (9:02)

- The Twinery Cookbook – Instructions for using Twine from simple to complex storybuilding

- Github – A space to practice coding and host your own HTML pages (optional) If you like, you can use this to publish your Twine story so that people can interact with it.

- Itch.io – If you’re a game developer you can use this platform to host your Twine story.

- Free Streaming Video Hosting – A (somewhat biased) list of free platforms for hosting and sharing your video

Storytelling

Digital storytelling is not about creating media – it’s about creating meaning.

Silvia Rosenthal Tolisano

We’ve all felt the pull of a good story – the feeling of inhabiting an experience different from our own or the recognition of familiar thoughts and feelings. Scientists have long suspected that there’s a lot going on in the brain when we hear a story. Today neuroscientists have been able to track which parts of the brain are activated when we listen to a story.

When a word like ‘cinnamon’ is used in a story, the part of our brains that is triggered by smell lights up. When someone describes something in vivid visual terms, the part of our brains that processes visual input is triggered (Chow et al., 2014). Metaphors that use texture, like ‘leathery hands’ or ‘velvet voice’, affect the sensory cortex, responsible for processing touch (Gonzalez et al., 2006). Stories that describe motion can create activity in the motor cortex, which controls body movements. A story with an emotional pull has been shown to trigger the same brain responses in the audience as in the storyteller (Boulanger et al., 2009).

When babies’ brains are first developing, it takes some time to develop what neuroscientists call ‘a theory of mind’ – the ability to recognize that others have thoughts and feelings separate from their own. Recent research has shown that people who read, watch or hear stories have a greater capacity for this theory of mind, and with it, an enhanced ability to navigate interactions with other people (Oatley & Mar, 2009).

Storytelling, or narrative presentation, has also been shown to increase memory retention of key information by a significant margin. This applies to both written stories and oral and visual presentations. Learners are not only more engaged and more likely to be motivated to change their behaviour, they’re also more likely to remember the information in the long term (Glonek et al., 2014).

So what does all this research mean for teaching and learning? It means that we can help learners imagine new experiences, inspire empathy and promote understanding by using the power of storytelling. We can help learners imagine situations that they haven’t yet encountered, put information in context and hold on to key messages longer. In our media and multimedia learning design, we can use storytelling techniques to create more effective, engaging learning with a greater long-term impact.

Creating Video for Learning

The first educational videos were created in the early 1900s starting with news reels, videos that were created to be played in movie theatres showing black and white footage of important events of the day (Ferster, 2016). Since then, the use of video for educational purposes has exploded, with multiple genres and applications evolving to fit particular learning needs.

Capturing and editing new video specific to your learners’ needs can enhance your course or lesson but it also requires a significant investment of resources – both from you and your students – so it pays to be strategic when making choices about how to present your content and focus video on the places where it will have the greatest impact.

So when is it a good idea to use video?

- When you need to tell a story. Adding video and audio can increase engagement in an important story.

- When you have access to experts. Well-edited interviews and panel discussions can be a rich source of content for your course.

- When your topic is inherently visual. A picture, especially an animated picture, can be worth a thousand words.

- When you want to add to your teaching presence. Video can add a human element to an otherwise asynchronous learning experience.

- When your learners need flexible access. The ability to watch and re-watch video at their own pace can be helpful to learners who are working on a new concept.

- When your learners need to retain key information. Short, well-edited videos have been shown to aid in the retention of information.

These guidelines for creating educational video will help you apply the principles we’ve been exploring to your own videos.

| Guidelines | Principles |

| 1. Keep it Short Research has shown that learners are most likely to retain the content of a video if it is less than 5 minutes in length. Shorter videos also allow users to choose the topic or subtopic they want to focus on, rather than searching through a lot of unrelated video to find what they need. | Mayer’s Segmenting Principle |

| 2. Focus on Learning Outcomes Make sure that your videos are focused and relevant to the course. | Mayer’s Coherence Principle |

| 3. Use a Conversational Tone When you narrate your video, use a friendly, enthusiastic, conversational tone. | Mayer’s Personalization Principle |

| 4. Include Active Learning Engage the learner in active learning by posing questions and asking them to solve problems or consider alternatives. | Merrill’s First Principles (Problem-centred application) |

| 5. Add Visual Elements To emphasize key points in your video, add visual elements like diagrams, text call outs and short clips from other sources. | Mayer’s Signalling principle |

| 6. Keep Text and Images Together Present images and text next to each other on screen rather than one at a time. | Mayer’s Spatial and Temporal Contiguity principles |

| 7. Build in Accessibility Ensure that you include captions, transcripts and descriptive audio wherever possible. | UDL Guidelines |

Storyboarding and Scriptwriting

An unscripted video wastes time, takes too much effort, and is painful to watch.

justin simon

It can be tempting sometimes to just jump into filming. But preparation and planning will save you time, ensure that your message is clear and in alignment with your learning outcomes and avoid unnecessarily long videos. Writing a script and creating a storyboard will give you a road map to follow as you create and edit your video.

Use clear, informal language and create a clear structure for your script with an introduction and conclusion. Read your script aloud to check that it is engaging, conveys your core message and flows naturally. This is also the best way to spot repetition and awkward wording. Practice a few times before you start recording.

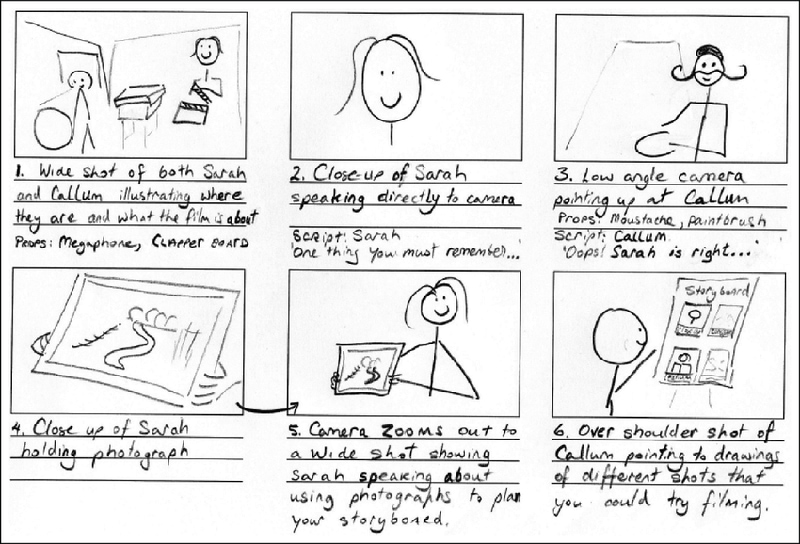

Storyboarding is the process of creating a map for producing and editing a video. It can be as simple or complex as you need it to be, including just text and description or images and sketch notes – whatever works for your video. Start a new row every time you change the shot.

The storyboard not only helps you set up shots efficiently, it also saves a lot of time when it comes to editing. With the storyboard in hand you will know exactly when to cut, overlay or edit a piece of video into the shot.

Explore: Twine and Video Creation

Twine

Twine / An open-source tool for telling interactive, nonlinear stories (twinery.org)

Non-linear branched narratives are a feature of video games and many new forms of storytelling. They can also be powerful learning experiences, allowing users to rehearse high stakes decisions and refine their responses. Twine is an environment where you can build models of branched ‘choose your own adventure’ type stories and get a bird’s eye view of the action. Try it out and see how complex these narratives can get! To allow users to play your Twine stories, you’ll need to download the HTML file and publish it somewhere like Github or Itch.io. Otherwise you can take screenshots of your story with all of its branches on Twine.

Creating Video for Learning

Your final group project should include some video that you’ve captured outside of simple screencasting. This can be as simple or complex as you are ready to tackle given the equipment you have at hand but try to move beyond the screencast approach we’ve explored already. Capture video away from the screen so that you can experience the challenges of lighting and sound capture in another space. The tutorial for Filming and Editing video will give you some ideas of the free tools available to use to edit your short video including:

Shotcut – a free, open source, multi-platform video editor

iMovie – for Mac users, this is built into your operating system. There’s also a Windows compatible version.

Echo360 (available in Brightspace under Course Tools) – you can capture, edit and stream your video from this platform but before you lose access to Brightspace, you need to download it and save it elsewhere.

Many of the screencasting tools that we used in Module 1 also allow you to capture and edit your own video.

Where can you stream a video for your website?

Hosting videos on your own WordPress site is not a good idea because the large file size can negatively impact the performance of your site and the OpenETC server. Echo360 (available through Brightspace) will deliver video that adapts to the bandwidth of your viewers and won’t slow down the loading of your WordPress site. However, you will need to download the video before you leave UVic to maintain access to it. Here are some other platforms that you can investigate:

Reflections

Choose one or more of these questions to help inspire your blog post for this module or share your own insights into the topic. Include a screenshot or link to a simple story you’ve created in Twine. You’ll be sharing your reflections on creating video in your Assignment 2: Video for a Learning Purpose post.

- Describe a meaningful learning experience that started with a story that you heard. What made it impactful for you? What senses did it appeal to? Did you recognize any of the storytelling techniques reviewed this week?

- In the reading this week, 7 Storytelling Techniques Used by the Most Inspiring TED Presenters, which of the presenters did you find most compelling? What technique(s) did you recognize in their talk?

- What storytelling techniques have you used instinctively and which ones require more work for you? Which techniques will you focus on moving forward?

- What learning experience does a branched narrative like Twine provide for learners? Where else do you come across branched narratives?

- What was the experience like capturing video away from the screencast? What did you find challenging and what was easier for you? What would you do differently next time?

To Do

- Read/watch the weekly Announcements forum posts in Brightspace (or in your email inbox if your notifications are set up that way).

- Sign up for Twine and create a simple branched story. Take a couple of screenshots for your blog or set it up on Github (optional) or another HTML platform so that you can link to the interactive version in your blog post

- Use some kind of video capture device (could be your phone, your laptop, or a digital camera) to create a short video for a learning purpose and include it in your blog post. Be sure to include your script and simple storyboard as well. This is not a screencast – make sure that you capture some footage away from the screen.

- Create a blog post and comment on your classmate’s posts for this module. Use the Reflection questions as inspiration or choose your own reflections to explore.

References

Looking for a deeper dive into some of these ideas? Check out some of the references below.

Boulenger, Véronique, Olaf Hauk, Friedemann Pulvermüller, Grasping Ideas with the Motor System: Semantic Somatotopy in Idiom Comprehension, Cerebral Cortex, Volume 19, Issue 8, August 2009, Pages 1905–1914, https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhn217

Chow, H. M., Mar, R. A., Xu, Y., Liu, S., Wagage, S., & Braun, A. R. (2014). Embodied comprehension of stories: interactions between language regions and modality-specific neural systems. Journal of cognitive neuroscience, 26(2), 279-295.

Ferster, Bill (2016-11-15). Sage on the screen : education, media, and how we learn. ISBN 9781421421261. OCLC 965172146.

Glonek, Katie L. & Paul E. King (2014) Listening to Narratives: An Experimental Examination of Storytelling in the Classroom, International Journal of Listening, 28:1, 32-46, DOI: 10.1080/10904018.2014.861302

González, Julio, Alfonso Barros-Loscertales, Friedemann Pulvermüller, Vanessa Meseguer, Ana Sanjuán, Vicente Belloch, César Ávila, Reading cinnamon activates olfactory brain regions, NeuroImage, Volume 32, Issue 2, 2006, Pages 906-912, ISSN 1053-8119, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.03.037.

University of Edinburgh, How to Create Video for Online Learning from the University of Edinburgh. © University of Edinburgh, 2021, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0