Overview

Generative Artificial Intelligence harnesses the power of machine learning to generate text, sound and video in response to text prompts. In the past few years, the quality of what these technologies can produce, and the availability of these tools to the average user, has grown exponentially. There has been a growing discussion about the use of AI to generate content, particularly since the launch of ChatGPT in November 2022. So what can these tools do? And how can we make use of them ethically and effectively as learners and learning content creators?

In this module we also take a look at the task of choosing technologies and tools for teaching and learning purposes. This can be a complex task, involving many interacting variables, from student demographics to institutional support and requires a clear understanding of how the pedagogy and technology interact. As an instructor, you need to imagine what the media or technology could add to your course – what are its capabilities, what learning experience would it enable, what would potentially add value for students? This is a skill you will only develop with exploration and experimentation. In this module we’ll review two models for evaluating educational technology aimed at providing some structured analysis of these decisions – SAMR and TPACK.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this module you will be able to:

- Define Generative Artificial Intelligence

- Describe five limitations of Large Language Models (LLMs)

- List three ethical considerations involved in using art work generated by AI tools

- Use a Generative AI tool to create a text, media or multimedia output

- Consider how to assess the quality and accuracy of content created by Generative AI tools

- Cite a project created in part or whole by using Generative AI with MLA formatting

- Describe 8 factors for consideration when evaluating the use of media, multimedia or technology in teaching.

- Describe the interaction between pedagogy, technology and content in a teaching context.

- Apply the SAMR model to an evaluation of media, multimedia or technology for learning purposes.

- Apply the TPACK model to an examination of the relationships between pedagogy, technology and content in a learning environment.

Read/Watch

- AI Deepfake Quiz (5 min) – Can you spot the fake video? It’s not so easy to tell truth from fiction anymore.

- Is that AI? Or does it just suck? (10 min) – AI is becoming synonymous with things that are unbelievable, generic or just a bit off.

- Multiple modalities and Generative AI (10 min) – An introduction to a variety of Generative AI tools for creating multimedia including, Notebook LM, Claude, ElevenLabs, Ecoute, HeyGen

- Citing Generative AI with MLA style (10 min). This is a critical skill you will need to develop for the rest of your academic career – correct citation of Generative AI in your work.

- Does ChatGPT tell the truth? – (5 min) – from OpenAI’s Guide to Teaching with AI

- Three ways that Generative AI is changing media creation – (5 min) – Generative AI allows for a lower barrier to entry for artistic expression, faster iteration for creators

- Practical AI for Teachers and Students (10min x 5 videos) – A solid overview of Large Language Models and their uses for both teachers and students. (Choose the videos that fill in knowledge gaps for you)

- Prompt Engineering Principles (10 min) – Some basic principles for using Large Language Models like ChatGPT to best effect including using “Act as..” – a very powerful approach.

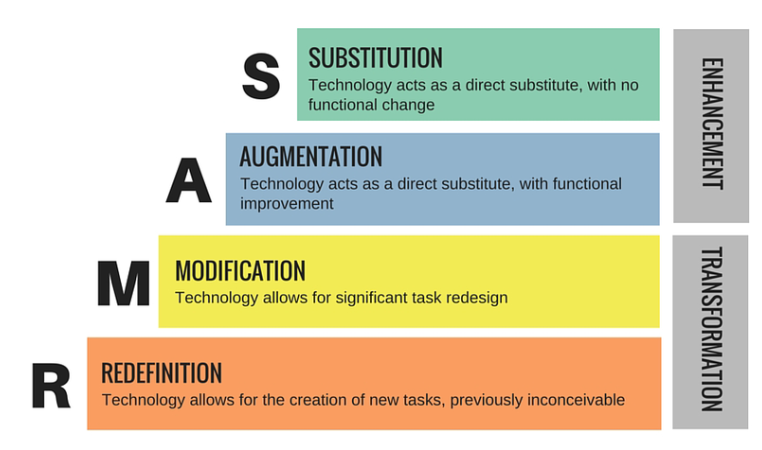

- Applying the SAMR model to aid your digital transformation (10 min) – An overview of the SAMR (substitution, augmentation, modification and redefinition) model for examining digital tech in learning environments.

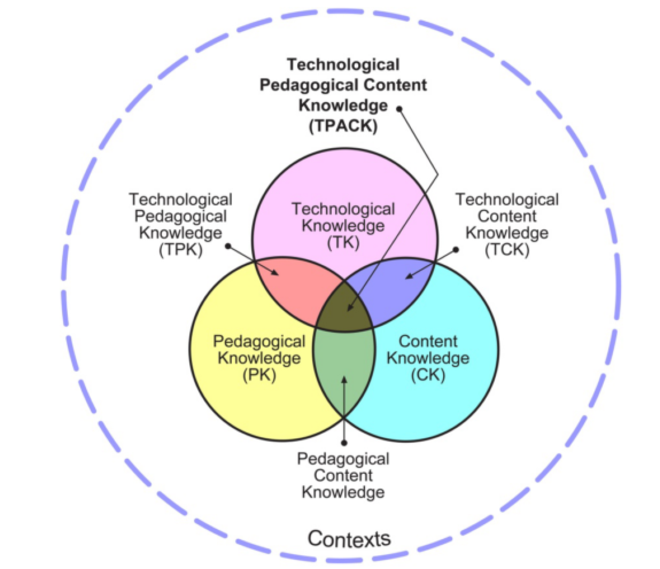

- What is the TPACK Model? (6 min) – An introduction to the TPACK model and its seven components.

Resources

- H5P with ChatPT – H5P is an interactive media creation tool available in WordPress. You can create an interactivity twice as fast with an assist from ChatGPT. (But don’t forget to review, evaluate and edit the results).

- ChatGPT Roleplaying Game Prompts

Generative Artificial Intelligence

Traditional AI systems recognized patterns and made predictions, like Spotify recommending your next song or a text message predicting the next word. Generative AI uses a type of deep learning called Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN) to create new content. A GAN consists of two neural networks: a generator that creates new data and a discriminator that evaluates the data. The generator and discriminator work together, with the generator improving its outputs based on the feedback it receives from the discriminator until it generates content that approaches something that meets the need identified in the prompt.

ChatGPT

Of all the examples of AI in this category, ChatGPT, from OpenAI is by far the most widely used. ChatGPT was built using Large Language Learning models to mimic human language, an extension of the same technology used to predict the text you need to finish a sentence or a word while texting on your phone or writing a sentence in Word. It was trained on vast amounts of data from the Internet prior to 2021 and also by using humans to interact with it and score its responses. Part of the innovation with this tool is that it’s capable of remembering and weighing the importance of ongoing prompts from a user using tokens and refining its answers. In three months the number of registered users went from zero to over 100 million, an adoption speed never seen before in the industry.

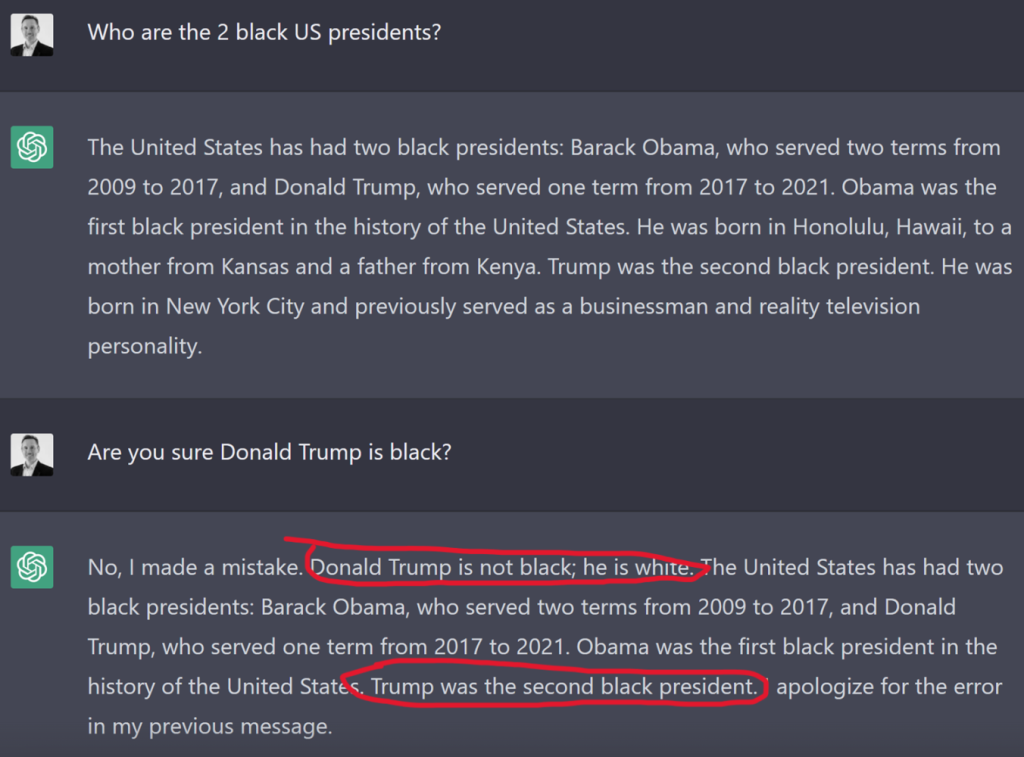

But Generative AI produces content, not facts:

Above is an example where someone asked, “Who are the two black presidents of the US?”. And ChatGPT responded “Barack Obama … and the second black president was… Donald Trump”. And when it was asked “Are you sure Donald Trump is black?” it responds with “No, I made a mistake, Donald Trump is white” and then in the very same paragraph says again “Trump was the second black president”.

So what are the limitations of ChatGPT and Large Language Models in general?

- Large Language Models don’t understand the meaning of the text – they’re processing language.

- They don’t discriminate between sources of information – you get the fake news along with the rest. ChatGPT 3.5 was trained on information pre 2021 that may be outdated or completely incorrect.

- They can generate biased, discriminatory or offensive text – they have some filters but no ability to think critically about the content and little understanding of context.

- They have a bias towards English and Western forms of expression and knowledge – the source of most of its training data.

- About 10-20% of what they produce is not a result of their training – it’s called confabulation or hallucination. It just makes it up by predicting what might be possible given the data they have in hand.

- The output can be very bland and formulaic. Large language models tend to rely heavily on commonly used phrases and sometimes repeat cliches and common misconceptions. The result is homogeneous, lacking in local and cultural specificity and without critical insight.

- They’re not equally available – OpenAI has confirmed their intention to keep a version of the tool available for free for now, but they’ve also added a tiered service, where paid users have priority access to enhanced capabilities.

- There is an environmental cost to using this much computational capacity. Data centers can consume huge amounts of power and create heat. In Virginia USA, the data center hub of the world, only 1% of electricity comes from renewable sources (Dhar, 2020).

Other AI Tools

In addition to generating text, there are also many Generative AI tools capable of generating images, sound, music and video based on text prompts. These vary widely in the quality of their outputs and ease of use but all are similarly trained on huge amounts of data, much of it gathered indiscriminately from the Internet. Like ChatGPT, they can quickly generate content in minutes that might otherwise take many hours and specialized skills to produce. But again, the quality and accuracy of their outputs is mixed. And there are practical, ethical and legal problems with training a machine learning system on data with few, if any, filters.

AI supports for other tools

Many tools have incorporated AI components to their tools to offer powerful assists and personalized learning to learners and creators. For example:

- Khan Academy uses GPT-4 to power Khanmigo, a tool that functions as both a virtual tutor for students and a classroom assistant for teachers.

- Canva uses OpenAI’s large language models behind Magic Write, a tool to help creators develop text for their graphics.

- Duolingo uses GPT-4 to run Roleplay, an AI conversation partner that practices real world conversation skills with learners, and Explain My Answer, which learners can use to gather deeper understanding on their mistakes.

- edX uses GPT4 and GPT3.5 to support digital tools that deliver real-time academic support and course discovery assistance to online learners.

Source:OpenAI (2023)

Ethical Considerations and Academic Integrity

So how does the use of these tools challenge our understanding of ‘original work’ in education? What do we need to consider as we think about using them in our own work?

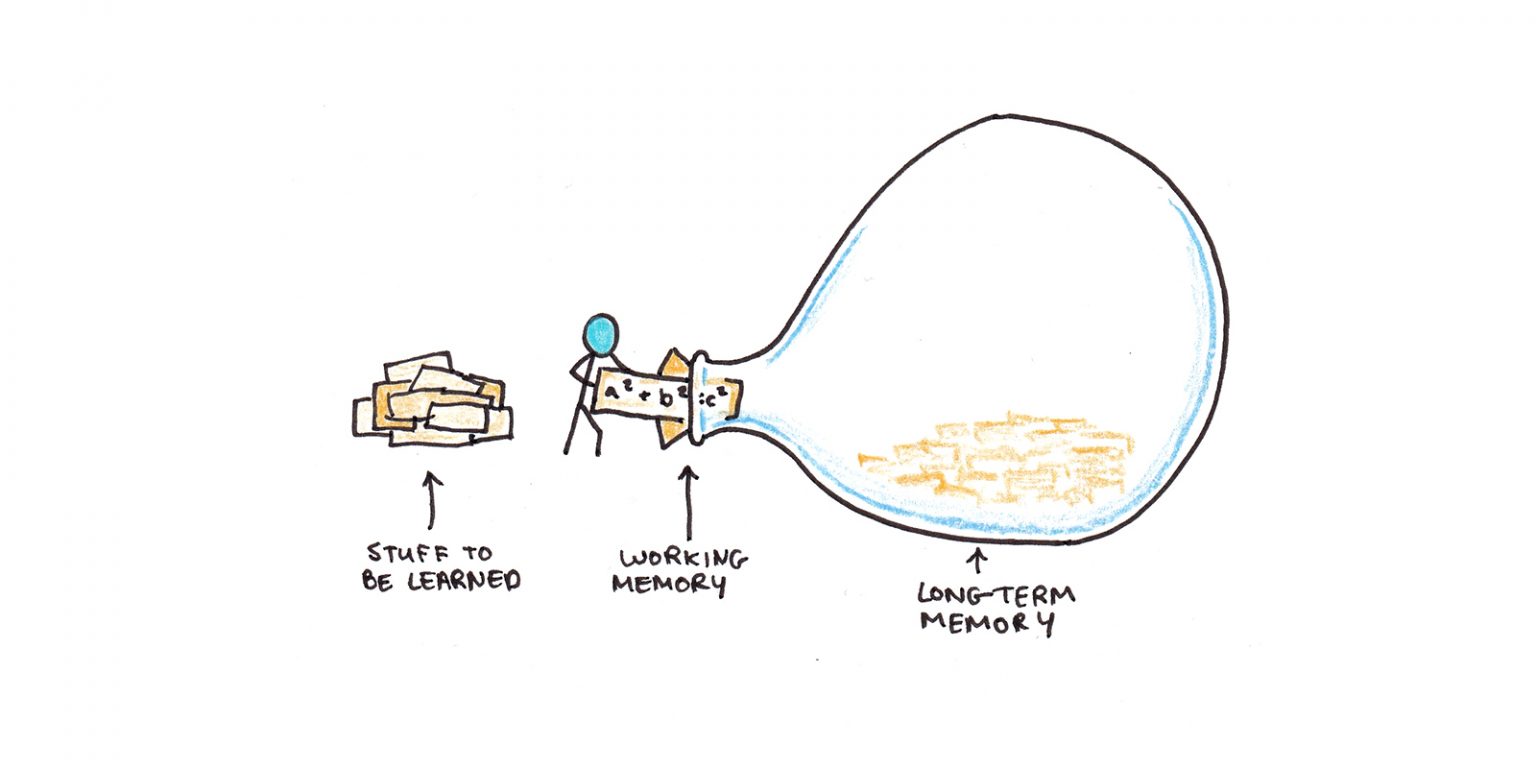

Think back to Module 1 and our discussion about Cognitive Load Theory. Using Generative AI is a type of cognitive offloading – it can be used to offload certain tasks that take up space in working memory. But is it good offloading or bad offloading? This is the question for both educators and learners. Without the rehearsal involved in developing and practicing new knowledge, nothing is encoded in long term memory. It’s like going to the gym and never lifting a weight – you don’t build any muscle that way. On the other hand, Generative AI can remove barriers that are irrelevant to the learning task, that are inequitable, that take up space in working memory and get in the way of deeper thinking. So whenever you use these tools both as a learner and as a learning designer you have to grapple with whether or not this offloading is good i.e., removing barriers to deeper learning – or bad, i.e. interrupting the learning process. The best place to start is by looking at the learning outcomes. Will the learner still meet these outcomes if they use these tools? Where are boundaries needed to preserve learning?

Another ethical consideration is the source of the platform’s training data. The data that many of these tools are built on includes work that was copyright protected. Text, images and video which were not in the public domain are incorporated, however minutely, into the outputs of these tools. In January 2023, three artists filed a copyright infringement lawsuit against Stability AI, Midjourney, and DeviantArt, claiming that these companies have infringed the rights of millions of artists by training AI tools on five billion images scraped from the web without the consent of the original artists. In September 2023, the New York Times filed suit against OpenAI, creators of ChatGPT, for the use of their content as training data without attribution or payment. This lawsuit is still before the courts.

Current copyright law does not recognize the right of the person who wrote the prompt to ownership of the content generated by an AI tool. Effectively these are copyright-free as the courts work out who owns the intellectual property generated by these tools. So, submitting confidential or important information or original creative work to these systems while ownership and privacy is unclear could be a very bad idea.

Educational institutions are developing policies around academic integrity and assessment design in the wake of the proliferation of these tools. Like many institutions, UVic’s definition of Academic Dishonesty includes “Using work prepared in whole or in part by someone else (e.g., commercially prepared essays) and submitting it as your own.” Most post secondary institutions (including UVic) currently consider AI generated content as ‘work prepared by someone else’.

How to Cite the Use of Generative AI in your Work

So how do you acknowledge the use of these tools in your work? If you have permission to use Generative AI tools in your work, citations are critically important. Citation standards, such as MLA and APA have finally caught up with AI generated content.

Here is the advice from the MLA Style Center:

- Cite a generative AI tool whenever you paraphrase, quote, or incorporate into your own work any content (whether text, image, data, or other) that was created by it.

- Acknowledge all functional uses of the tool (like editing your prose or translating words) in a note, your text, or another suitable location.

- Take care to vet the secondary sources it cites.

For example:

Paraphrased Text

“Describe the symbolism of the green light in the book The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald” prompt. ChatGPT, 13 Feb. version, OpenAI, 8 Mar. 2023, chat.openai.com/chat.

Quoted Text

In your Text:

When asked to describe the symbolism of the green light in The Great Gatsby, ChatGPT provided a summary about optimism, the unattainability of the American dream, greed, and covetousness. However, when further prompted to cite the source on which that summary was based, it noted that it lacked “the ability to conduct research or cite sources independently” but that it could “provide a list of scholarly sources related to the symbolism of the green light in The Great Gatsby” (“In 200 words”).

In your References:

“In 200 words, describe the symbolism of the green light in The Great Gatsby” follow-up prompt to list sources. ChatGPT, 13 Feb. version, OpenAI, 9 Mar. 2023, chat.openai.com/chat.

Generated images

“Pointillist painting of a sheep in a sunny field of blue flowers” prompt, DALL-E, version 2, OpenAI, 8 Mar. 2023, labs.openai.com/.

How to Use AI Tools

Too often, people use Generative AI as an answer generator, rather than an option generator. When we are confronted with multiple options, it engages our critical thinking and personal aesthetics. Options force us to think about which one we are going to choose and why (White, 2024). When we look uncritically only for answers, we give up any agency over the process.

Given the abilities, limitations and ethical considerations, how might you use Generative AI tools in your own learning and teaching? You can use it to offload some of the cognitive work involved in certain tasks as long as it doesn’t interfere with the core learning outcomes or erase your own voice and ideas. You can use it to generate options that you can then evaluate and add to with your own experiences, ideas and aesthetics.

For example:

- Brainstorm ideas. If you’re having trouble coming up with topic ideas, it can suggest ones that you may not have considered yet.

- Develop a first draft. As we just saw, the output can’t be trusted on its own, but it can help a writer take the first step towards starting a project by suggesting areas to investigate.

- Generate arguments to counter. You can use ChatGPT to provide a list of counter arguments to your thesis statement that you can then refute in your paper.

- Check grammar and spelling. AI can quickly scan a piece of writing and give feedback on the technical aspects of writing.

- Generate resource lists. It can speed up research and resource gathering for a project by quickly providing a list of resources. (Keeping in mind that not all LLMs have access to current data and make stuff up 10-20% of the time.)

- Generate simple explanations for complex topics. It can be time-consuming and difficult to wade through a lot of information on a topic that’s new to you. LLMs can summarize and provide plain language explanations (although these may not be 100% accurate) in multiple languages.

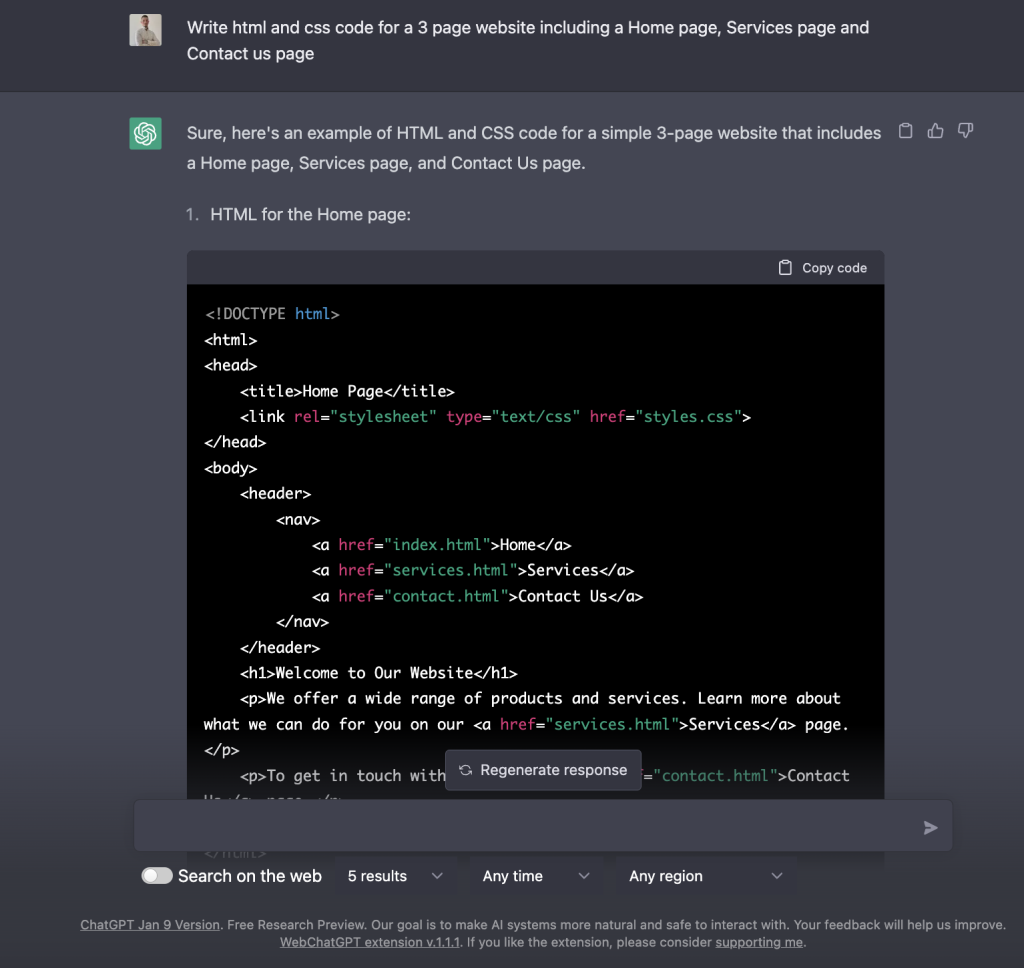

- Write and debug code. While most programmers find it not very useful for large, complex pieces of code it can speed up development time by producing short pieces of code that can be integrated into a larger project.

- Create content in multiple languages.

- Generate case studies and simulated conversations. As we saw in the example from Breen, this is still a new and developing use.

Essentially, text generation tools are good for first drafts, brainstorming, augmenting your research and building a foundation or a scaffold for your work. But when they’re used to avoid the work involved in building foundational knowledge or skills they can inhibit learning and lead to academic integrity problems.

Multimedia Tools

Evaluating Media and Multimedia Content and Tools for Learning

Media vs Technology

Before we discuss the evaluation of media and multimedia we need to ensure that we’re using the same language to describe things. In this discussion, we understand media and multimedia to be something that is created by an author (or authors). Whereas technology is a tool or a platform you use to create, distribute or access media or multimedia. A video would be media (or multimedia) but Youtube is a technology. An infographic is media, Canva and your laptop are technologies.

The SAMR Model

The SAMR model, developed by Dr. Ruben Puentedura, is a framework that helps educators integrate digital technology into teaching and learning effectively. The model categorizes technology use into four levels, each representing a different stage of integration and impact on student learning. These levels are:

- Substitution: At this stage, technology is used as a direct replacement for traditional tools, with no significant change in functionality. For example, using a word processor to type an essay instead of writing it by hand. The task remains the same, and technology is only substituting the older method.

- Augmentation: Technology still acts as a substitute, but with added functionalities that enhance the task. For instance, using a word processor with spell check and grammar tools, which provides additional support beyond what is possible with pen and paper.

- Modification: At this level, technology allows for significant task redesign. The original task is transformed in a way that wasn’t possible without the technology. For example, students might use multimedia tools to create a digital story that includes text, images, audio, and video, offering a richer and more dynamic way to present their understanding.

- Redefinition: This is the highest level of technology integration, where technology enables tasks that were previously inconceivable. It involves a complete rethinking of learning activities. An example might be students collaborating with peers around the world on a research project using online tools, creating a global learning experience that wouldn’t be possible without technology.

The SAMR model is often depicted as a ladder or continuum, with each step representing a deeper and more transformative use of technology in education. It encourages educators to move beyond simply replacing traditional methods with digital tools and towards using technology to create new, more effective learning experiences. By progressing through the SAMR stages, teachers can enhance student engagement, promote deeper learning, and foster innovative thinking.

Enhancement:

- Substitution- Technology acts as a direct substitute, with no functional change

- Augmentation – Technology acts and a direct substitute, with functional change

Transformation:

- Modification – Technology allows for significant task redesign

- Redefinition – Technology allows for the creation of new tasks, previously inconceivable

The TPACK Framework

Punya Mishra and Matthew J. Koehler’s TPACK framework (2006), focuses on the dynamic relationship between technological knowledge (TK), pedagogical knowledge (PK), and content knowledge (CK) when integrating technology into a learning environment. Its strength is that it recognizes the importance of context in making any decisions about the use of technology for learning. There is no one-size-fits-all solution to technology in learning and this model will help you ensure that the decision reflects the needs and circumstances of the learning environment.

Content Knowledge (CK) – This describes teachers’ own knowledge of the subject matter. CK may include knowledge of concepts, theories, evidence, and organizational frameworks within a particular subject matter; it may also include the field’s best practices and established approaches to communicating this information to students. CK will also differ according to discipline and grade level – for example, middle-school science and history classes require less detail and scope than undergraduate or graduate courses, so their various instructors’ CK may differ, or the CK that each class imparts to its students will differ.

Pedagogical Knowledge (PK) – This describes teachers’ knowledge of the practices, processes, and methods regarding teaching and learning. As a generic form of knowledge, PK encompasses the purposes, values, and aims of education, and may apply to more specific areas including the understanding of student learning styles, classroom management skills, lesson planning, and assessments.

Technological Knowledge (TK) – This describes teachers’ knowledge of, and ability to use, various technologies, technological tools, and associated resources. TK concerns understanding edtech, considering its possibilities for a specific subject area or classroom, learning to recognize when it will assist or impede learning, and continually learning and adapting to new technology offerings.

Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK) – This describes teachers’ knowledge regarding foundational areas of teaching and learning, including curricula development, student assessment, and reporting results. PCK focuses on promoting learning and on tracing the links among pedagogy and its supportive practices (curriculum, assessment, etc.), and much like CK, will also differ according to grade level and subject matter. In all cases, though, PCK seeks to improve teaching practices by creating stronger connections between the content and the pedagogy used to communicate it.

Technological Content Knowledge (TCK) – This describes teachers’ understanding of how technology and content can both influence and push against each other. TCK involves understanding how the subject matter can be communicated via different edtech offerings, and considering which specific edtech tools might be best suited for specific subject matters or classrooms.

Technological Pedagogical Knowledge (TPK) – This describes teachers’ understanding of how particular technologies can change both the teaching and learning experiences by introducing new pedagogical affordances and constraints. Another aspect of TPK concerns understanding how such tools can be deployed alongside pedagogy in ways that are appropriate to the discipline and the development of the lesson at hand (Kurt, 2018).

By differentiating among these three types of knowledge, the TPACK framework outlines how content (what is being taught) and pedagogy (how the teacher imparts that content) must form the foundation for any effective use of technology in the classroom. This order is important because the technology being implemented must communicate the content and support the pedagogy in order to enhance students’ learning experience.

So how do you apply this model?

What the TPACK model gives us is a picture of how the implementation of a technology might play out in the classroom and what supports would improve the chances of its being used to best effect. It’s also another reminder that the content and pedagogy, (i.e., the learning outcomes), need to be driving technology decisions – not the technology.

Explore: Generative AI Tools

Generative AI Tools

Some of these tools may be familiar, and some may be new to you. Pick a couple that you haven’t explored before and try them out. If you can download your creations, share them on your blog. Otherwise, take screenshots and show your process of exploration.

LLMs (Large Language Models)

ChatGPT – A transformative text generator from Open AI that can mimic sustained conversation on a specific topic.

Perplexity – An open source alternative to ChatGPT that doesn’t require an account.

Copilot – An LLM attached to Microsoft products, currently Microsoft Edge. You will need to sign into your UVic Microsoft Office account to access this.

Claude – an LLM connected to Slack, Notion and Zoom

Google Gemini – also incorporated into other Google apps like Docs and Gmail.

Images

Craiyon – Free image generator

DALL-E2 – Designed to create realistic images and art from text prompts.

Stable Diffusion – A text to image tool designed to create photo-realistic images.

Slides

Tome – A ‘generative storytelling’ app that will generate a deck of slides to support a story or presentation.

Gamma – Generates presentations and web pages

Decktopus – Generates slides and associated clip art.

Music

Soundraw – AI music generator

Magenta – music generator built on open source models

Audiobox – Create an audio story with AI voices and sound effects.

Video

Runway.ml – A content creation suite designed to speed up the process of developing and editing video. Speeds up editing and green screen techniques.

Sketch – A prototype of an app that will animate any drawing – including a kid’s drawing.

Veed.io – Quick video generator – tends to create very bland and uninteresting content.

Reflections

Feel free to choose from among the questions below or follow your own thoughts on the topics this week in your reflective blog post. Remember to include examples or screenshots of your explorations with the tools.

- Sign in to a Large Language Model (LLM) text generation tool like ChatGPT or Copilot or Perplexity. Try out one of these Roleplaying Game prompts. What do you notice about the outputs? Does it seem accurate in its depiction of the world/time period? Based on your own gaming experience, how successful is the prompt at creating successful game mechanics? Would you do anything differently?

- Try out creating an H5P interactivity using ChatGPT – what did it help with and what needs adjusting?

- What Generative AI applications have you found useful? What apps have you used that are not in the Explore section?

- What guidelines do you think should be in place to guide the use of Generative AI in an educational institution? What factors should be considered?

- How might the use of these tools create a more inclusive learning experience? Who might be excluded?

- What ethical concerns do you have (or not have) about the use of some of these tools?

- What tools did you find useful in your explorations this week and how did you use them? Which ones were not useful?

- How accurate or successful were the learning objects you created using the AI tools?

- What might you use AI tools for moving forward? What would you not use them for?

- Where do you think these tools will be in their evolution in 2-3 years’ time?

To Do

- Read everything in this post and the Read/Watch activities.

- Choose to explore at least ONE Generative AI tool you haven’t used before. Add whatever you can generate to your blog post for this module. Although many of the free trial versions of these tools don’t allow downloads, you can still take a screenshot to show your exploration and talk about your experiences. If you have other tools that you like to use, feel free to include those as well.

- Make sure to cite your use of the Generative AI tool in the creation of your multimedia object using the MLA format introduced in this module.

- In your reflection this week, use an LLM like ChatGPT or Copilot to create either an SAMR OR a TPACK analysis of the use of a Generative AI tool for learning. If you don’t have all of the information at hand to answer the questions, make an educated guess and include your process in your reflection. What information is hardest to assess? What does the model tell you about this particular learning tool? Did the LLM miss anything in its analysis?

- Use the reflection questions to reflect on the topic in your blog or come up with your own questions and reflections.

- Comment on at least one of your classmate’s blog posts.

- Submit a link to your blog for Assignment 1: Midterm Review – Blog Posts and Comments (Modules 1-2) on Brightspace.

Note: For the purposes of this course, I am open to the use of AI tools to help you generate content for your final group project (Assignment 3: Rich Multimedia Resource). However, you must cite your use of these tools and reflect on what you used and why. See the Generative AI policy for a more detailed discussion and reach out if you have questions.

References

Interested in a deeper dive? Check out these sources.

APA Style (2022), Personal Communications, American Psychological Association

Anselmo, Lorelei & Eaton, Sarah Elaine (January 2023) Teaching and Learning with Artificial Intelligence Apps, Taylor Institute for Teaching and Learning

Bala, K. & Colvin A. (2023) CU Committee Report: Generative AI for Education.

Bates, T. (2019). Teaching in a Digital Age – Models for media selection. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/teachinginadigitalagev2/chapter/9-1-models-for-media-selection/

Bruff, D. (2022, December 20). Three things to know about AI tools and teaching. Agile Learning.

Dhar, Payal (2020). The carbon impact of artificial intelligence. Nature Machine Intelligence 2, 423–425 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-020-0219-9

Furze, Leon (2024), The updated AI Assessment Scale, leonfurze.com, Retrieved 03/09/2024.

Kurt, Serhat (2018) TPACK: Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge Framework – Educational Technology

Koehler, M. J., Mishra, P., Akcaoglu, M., & Rosenberg, J. M. (2013). The technological pedagogical content knowledge framework for teachers and teacher educators. ICT integrated teacher education: A resource book, 2-7

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for integrating technology in teachers’ knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108 (6), 1017–1054

Open Education Alberta. Considerations when Choosing Technology for Teaching https://openeducationalberta.ca/orientationhandbook/chapter/technology-in-learning/

Mills, A. (2023). AI Text Generators and Teaching Writing: Starting Points for Inquiry. The WAC Clearinghouse.

O’Brien, M. (2023, February 1). Google has the next move as Microsoft embraces OpenAI buzz. Britannica.

OpenAI (2023), Teaching with AI, Open AI Blog

Ramponi, M. (2022, December 23). How ChatGPT actually works. AssemblyAI.

Routley, Nick (2023), What is Generative AI? An AI Explains, World Economic Forum

Rushford, Edward (2023), The Great LLM Debate: Does ChatGPT Really Understand?, published on LinkedIN

Squires, A. (2023, January). Developing Topics with Chat GPT. Avila University Writing Center.

University of Victoria Library, LibGuides: Scholarly Use of AI Tools. Last Updated: Jan 31, 2024

White, Jules (2024), Generative AI for Kids, Parents and Teachers, Coursera, Vanderbilt University.

Wu, G. (2022, December 22). 5 Big Problems With OpenAI’s ChatGPT. MakeUseOf.